Midsommar is the second feature from writer-director Ari Aster, following 2018’s Hereditary – a critically and commercially successful film considered by many as a modern horror masterpiece.

The movie begins with Dani (Florence Pugh), who just lost her parents and her sister in a tragedy. In the midst of mourning the loss of her loved ones, she tags along her boyfriend Christian (Jack Reynor) and his friends on a trip to Sweden to which they set out to conduct research on Hårga – a rural commune that one of their colleagues is a part of.

Dani, Christian, and his buddies arrive on the commune’s Swedish remote location on Dani’s birthday. However, the latter is by no means in a celebratory mood. She’s still going through a difficult time; aside from the fact that a family tragedy happened just recently, Christian is increasingly becoming emotionally distant. You see, Christian’s decision to bring Dani to the trip appears to be more of a chore, a responsibility induced by guilt, than an affectionate gesture.

Under these circumstances, Dani is faced with an even more difficult conundrum, with a series of horrible events unraveling in Hårga.

Hårga is a scenic hell

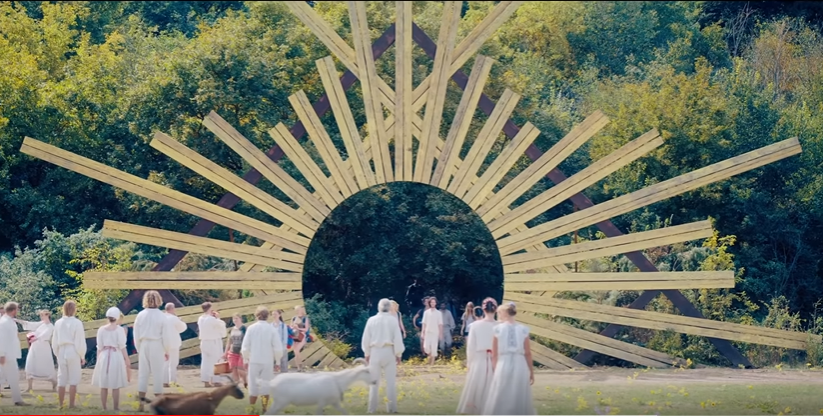

On the surface, Hårga looks perfect as far as weird folk communities are concerned. The commune stands in a picturesque location, and the facilities are quaintly designed. Meanwhile, the residents’ combined demeanor and physical appearance can be perceived as whimsically volatile. The women are like a group of Maria von Trapps on mushroom, and the men are a group of friendly but at times moody Kris Kristoffersons. Also, unlike Dani, the people are in a celebratory mood. Hårga just kicked off its midsummer festivity upon the arrival of the visitors, and it only happens every 90 years.

In the early scenes of the movie, the presentation of Hårga’s setting, its people, and its culture succeeds in setting up an eerie and unsettling atmosphere. While attractive on paper, hints of impending dread are also slowly and subtly inserted–a feeling that something horrific is just waiting to be unleashed insidiously.

Soon enough, they were presented with precarious, outrageous situations–starting off with two old people voluntarily throwing their bodies off a cliff. Surprisingly, while there are traces of shock and disbelief in the faces of the American visitors as they bear witness to a suicide ritual, they manage to be calm and collected for the most part. One of the older bystanders defends the ritual by saying that it’s not as extreme as it looks; for them, the more people age, the more they become corrupt, and so, Ättestupa should be performed by old people when they reach past 72 years old.

Similarly unorthodox rituals and practices, e.g., the serving of a pie laced with pubic hair and commune members crying in empathy with a visitor’s pain, will follow Ättestupa, evoking accelerating levels of unease as the movie progresses.

Isolation breeds desperation

When the film nears the third act, Dani has to find a way to keep her sanity while dealing with Hårga’s grotesque traditions, coinciding her bubbling emotional turmoil. Without revealing too much information, her state of mind at the end of the film could be viewed by some as baffling, especially if they weren’t able to fully empathize with her character.

It’s important to note that before the trip, Dani was put into a wringer due to a devastating loss, and to add insult to an already grave injury, her relationship with Christian is hanging by a thread. She feels alone, and this feeling brings about desperation. In a psychological perspective, lonely or troubled people, particularly the younger ones, submit to pressures in exchange for social rewards. Because being friends, or being part of something, is seen as very important, people tend to focus on the potential payoffs regardless of the risk that their decisions pose.

In comparison to Dani’s state of mind, Hårga’s grotesque customs become normalized to her as the movie slowly inches to conclusion. One of the possible explanations to this is Hårga’s presentation of a kind of relationship missing in her current life – a closely integrated one that, albeit twisted, is bound in love or genuine affection. It’s a kind of relationship that Christian cannot offer.

A nightmare in broad daylight

A lot of reviewers have called Midsommar a nightmare in broad daylight. In a literal sense, this is an appropriate description since the movie’s most horrific scenes and imagery take place while the sun is up. However, the said description also applies to the movie when we examine the idea of normal people making horrible decisions consciously and unapologetically.

Aside from Dani’s experience, other examples include scenes showing other main characters’ desensitization to Hårga’s atrocities. Seeing old people perform Ättestupa did not deter them from leaving Hårga, and in fact, the event even encouraged some of them to stay because of the academic value that it can bring to their research despite the moral, ethical, and legal issues that surround it. Other illustrations of the above-mentioned point involve few scenes where we see Christian’s friends disrespecting Hårga’s rules, which are actions considered illegal even in a civilized society.

Overall, Aster’s second feature is strange, horrifying, and thought-provoking. The movie has enough conventional horror tropes to be entertaining, but the discourse that can arise from both of its obvious and subtextual themes may even be more appealing.